It was December 1947. World War II had ended, but the Greek Civil War was just hitting its stride. Communists rebelling against the reign of King George II occupied the tiny village of Tsamantas, high in the Greek mountains and very close to the Albanian border.

An old man, the elder of the village, hurried to the house in the middle of the night. He pounded on the door with his walking stick. “Lamprini, Lamprini! Wake up!” he shouted. “You must gather your family and go! They have found out what you have done and they are coming for you!”

Lamprini and her sister Youla rushed to wake the children, three in all, grabbed what they could carry, and fled into the night on foot down the mountain. There was no time to lose.

But just what had Lamprini done?

The communists regularly demanded supplies from the villagers, things like flour and sugar. They thought Lamprini was rich (she had family in America, you know), so they made her bake them bread. They had given her a chit the day before with a number written in pencil — the number of loaves she was to make. But she’d recently gotten a care package from her father in America. It contained, among other bits and baubles, a pencil with an eraser. She’d carefully altered that scrap of paper so she had to make fewer loaves. That is what they discovered. And they were coming to punish her.

Lamprini carried their things and led the way. Her 4-year-old son and 2½-year-old daughter followed her. Youla, 8 months pregnant, brought up the rear, balancing Lamprini’s 8-month-old daughter on her belly. It was the start of a more than 30-mile trek to Igoumenitsa, where they would spend five years in a refugee camp on the eastern coast of Greece before they finally got their chance to come to America.

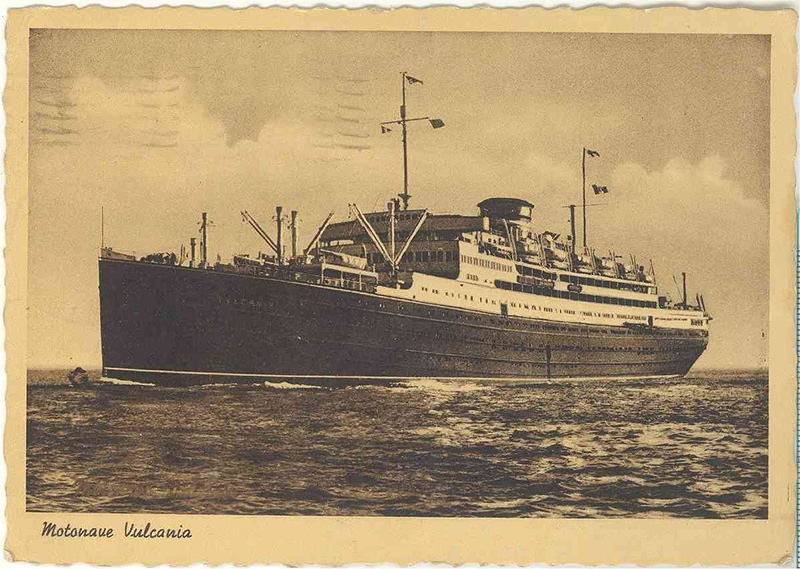

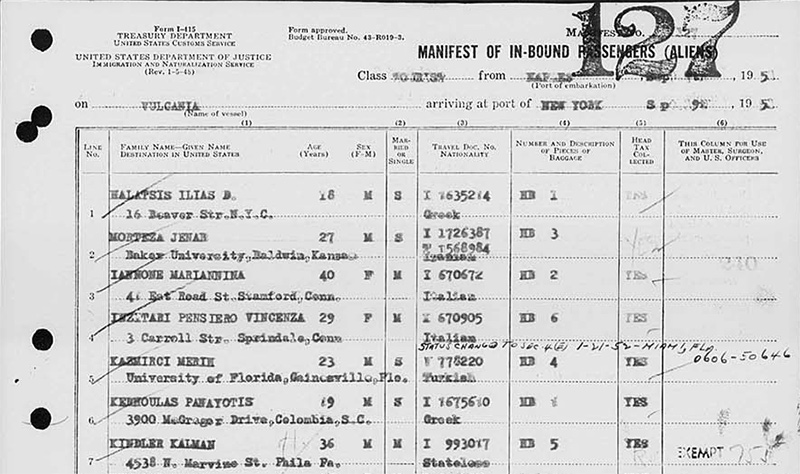

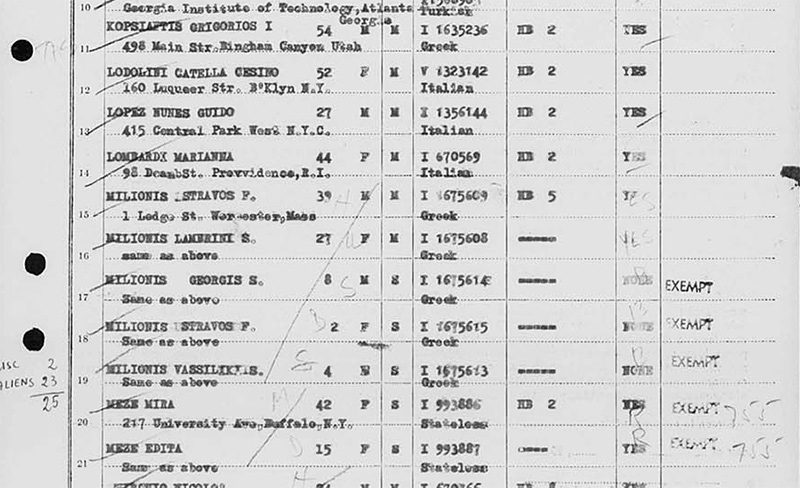

…. Or so the story goes. You know how family stories can be: The more often they’re told, the more they start sounding like a Steven Spielberg movie, with lots of big action, sweeping music, and shining lights. In this version, the story would end with the MS Vulcania docking at Ellis Island in September 1951 with Lamprini, Youla, and the children gathered at the bow, eyes shining as they saw America for the first time, Statue of Liberty backdrop and all.

Then there’s the truth, which exposes all that action, music, and lights as somewhat exaggerated or even apocryphal.

And it’s infinitely more interesting.

To learn the true story of that escape from Tsamantas, I sat down one afternoon with Bessie, the baby who rode to Igoumenitsa on her Aunt Youla’s pregnant belly in 1947, in her home in Sturbridge. She’s my de facto mother-in-law. She doesn’t have any memory of the journey itself, but she did know details that Lamprini, now remembered as “Big Yia Yia” — Great-Grandmother — after her passing two years ago, would share on the rare occasion she was willing to talk about that time.

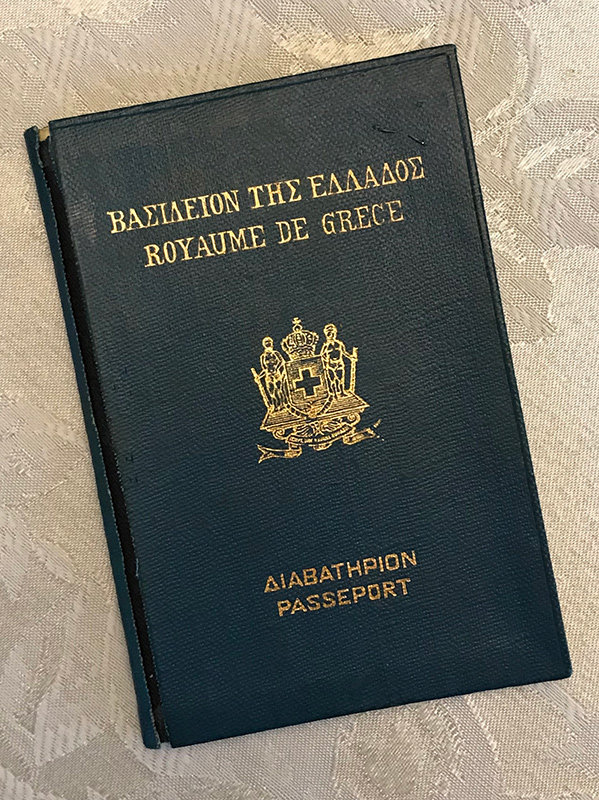

Bessie told me the story as she laid out artifacts — a passport with worn edges and a cracked spine that still carries the scent of her father’s tobacco; a long and faded government form filled with her grandfather’s tiny, cramped, but perfect handwriting; her mother’s hand-crank eggbeater with a worn wooden handle — on a dining room table set with white lace linens and littered with stained coffee cups and sticky cake crumbs after a family birthday celebration. She told it with quiet, teary remembrances, and from a place of deep gratitude. Bear with me — I’ll get to that soup recipe.

So, there was no old man/village elder with a walking stick. The communists were not coming for her. There was no frantic flight by night down the craggy mountain pass.

What really happened: It was broad daylight, and Lamprini had just finished baking the bread demanded by the communists in the outdoor oven. The loaves were cooling on the rocks nearby when word came from the kanthos, or center of town: The Hellenic Army — the king’s army — was coming, and the communists were fleeing! The ensuing chaos was Lamprini’s chance to escape with her family and reunite with her husband.

Lamprini and Youla hurriedly gathered supplies, loaded up the donkey, and shepherded three young children, aged 4 and under, 30 miles down the mountain and to Igoumenitsa, the trek made harder and longer because the 4-year-old would turn around and start walking back to the village. They spent five years in a refugee camp. They made it to America.

But what also happened is the part that sounds like it actually could be in a Spielberg movie: Lamprini really did get a pencil eraser in a care package from her father in America, and really did change the number on that scrap of paper. The number of loaves cooling on the rocks that day were not as many as she was ordered to make.

That’s pretty badass, right? A 22-year-old woman who grew up in a remote mountain village with three small children to care for and a husband still away after the war took an enormous risk so that she could have enough for her family (she was far from rich, of course). It could have ended with her execution, and maybe the execution of her entire family. The communists occupying the village weren’t just a bunch of strangers who moved in and took charge; they were village residents, people Lamprini had grown up with, people she’d known her whole life … and who knew her. And she still took that risk so that her family could survive. That is courage.

And I never realized this about her! I had no idea. All those times I heard the story, I got caught up in the Spielberg moments. When my boyfriend and I would visit Big Yia Yia, we’d sit in the dining room of her home on the outskirts of Worcester, surrounded by photos of her children and grandchildren and nieces and nephews, trying to communicate as best we could. Bessie acted as interpreter. Big Yia Yia would make us traditional dishes like pastitsio, tomato rice, and once — just once — avgolemono soup (and more on that later). She’d follow the meal with Greek coffees, and when our cups were down to the dregs, we’d flip them upside down on the saucers and wait for her to read us our “fortunes” from the dripping grounds. No matter what the pattern looked like, she’d always tell us the same thing: “I see … a party. I see family and dancing. It’s a wedding! You get married and have babies and I die relaxi.” This quaint and traditional — and, let’s be frank: stereotypical — scene was so wonderful and charming. But now I know: This yia yia was no simple old lady who only lived for babies and weddings. She was a fierce, determined, and (sorry, Bessie) a 100 percent badass.

We’ll never know if the communists figured out she’d altered the number. We do know, though, that the family boarded the MS Vulcania, arrived at Ellis Island, and settled in Worcester. We know that Big Yia Yia went to a lot of weddings and parties, and had a lot of babies to play with (11 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren in all, plus nieces and nephews and all their children). Her grandson and I don’t have any plans to get married, and we aren’t having any children. I do honestly believe, though, that she did die relaxi after leading an amazing life, one full of love and adventure and courage, but also of hardship and pain.

I wish I’d known the true story sooner. I might not have had the guts to ask her about it (OK, I totally wouldn’t have had the guts to ask her about it, especially since she didn’t like to talk about it herself), but being in her presence and knowing what she endured to give her family the American dream, knowing her immigrant story, would have reframed those few visits we had in a more personal, historical context. The pastitsio and the tomato rice she made for us — recipes that escaped the communists just like they did — would have tasted even better. And I would have started my pursuit of her avgolemono soup recipe much earlier.

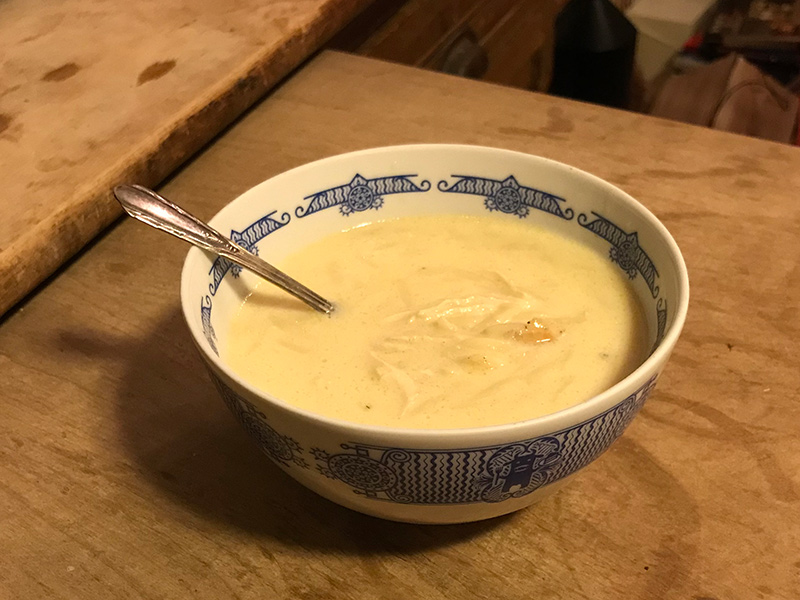

Big Yia Yia’s Avgolemono Soup

Avgo = egg; lemono = lemon. I’d been in New York City for over a decade by the time I met Big Yia Yia, and eaten at enough Greek diners to recognize the name of the dish. But the idea of it absolutely grossed me out — eggs? and lemon? in a soup? No thank you. But I am a polite guest, and was eager to earn points with both Big Yia Yia and Bessie, so I smiled and picked up my spoon.

This stuff is amazing. It hits so many textural points with its silky broth-and-egg mixture, chewy orzo, and moist, meaty shredded chicken. So many, it teeters on the edge of far too rich. But that’s where the lemon comes to the rescue — the ~pop~ of the acid keeps it bright and fresh, balancing out the heaviness.

This recipe was developed from notes on a worn index card generously shared by Bessie. She’d jotted them down originally for her husband when he was a chef at a local restaurant and had the crazy idea of making this soup for 50 people. It’s one of those classic, hand-me-down recipes without official weights and measures, so I had to do some detective work and testing. And even though she helped Big Yia Yia make it dozens of times, when Bessie made it herself, she had to do some translating, too. When she’d ask Big Yia Yia how much of something was going into the pot, she’d answer, hyedhi — “a handful,” or potiri — ”a glassful.” But whose hand? Which glass? The answer to that was, always, tha xerise — “you’ll know.”

Make the soup

In a large Dutch oven or soup pot, heat 10 cups chicken broth/stock (regular or low-sodium).

Just as it’s coming to a boil, add 6 tablespoons butter in chunks (salted or unsalted); stir to melt as it continues to come to a boil.

Add 1 brimming cup orzo (or pearl couscous or rice) and cook until almost tender; reduce heat and keep at a simmer.

Separate 5 eggs. In a large bowl, beat the egg whites with an electric mixer just until soft peaks form. Add the egg yolks, and beat on low until fully incorporated. Add juice from at least 2 lemons (more if you like it lemony like I do, but at least ½ cup of juice).

Scoop up 2 cups of the hot broth and slowly stir into the egg mixture. (Sigha sigha! — ”slowly, slowly!” This is very important, otherwise the soup will curdle.)

Pour egg mixture into the pot, and slowly stir to incorporate (it’ll be a bit foamy). Add shredded chicken (Big Yia Yia would, of course, boil a whole chicken, debone it, and add the meat back to the soup, making the chicken stock in the process), and stir it all together. Bring to a simmer, stirring regularly, till it’s hot-hot all the way through.

Ladle into bowls and serve with warm, crusty bread — the more rustic, the better. If you can get your hands on some authentic Greek barley rusks, setting one of those on top of the hot soup and giving it some time to soak up the silky broth till you can break it apart with your spoon will be totally worth it. But, confession time: My favorite way to eat this is to dunk diner-quality waffle fries in it.

And as you eat it, however you decide to eat it, remark on the labor involved in making it, and remember that badass Big Yia Yia did it all by hand — no electricity, no Kitchen Aid. She used that hand-crank beater, which Bessie still uses today.

Note

This is not one of those soups that gets better over time. Do not freeze it. The recipe yields around 4 quarts; what isn’t consumed the day you make it should be promptly cooled and refrigerated, and eaten up in the next day, maybe two. It will thicken significantly when cool, but should loosen up as you slowly reheat it. Stir it well as you do. If it’s nice and hot, but still too thick, add chicken broth a few tablespoons at a time until it’s back to your desired consistency.